By Koh Cheng Jin

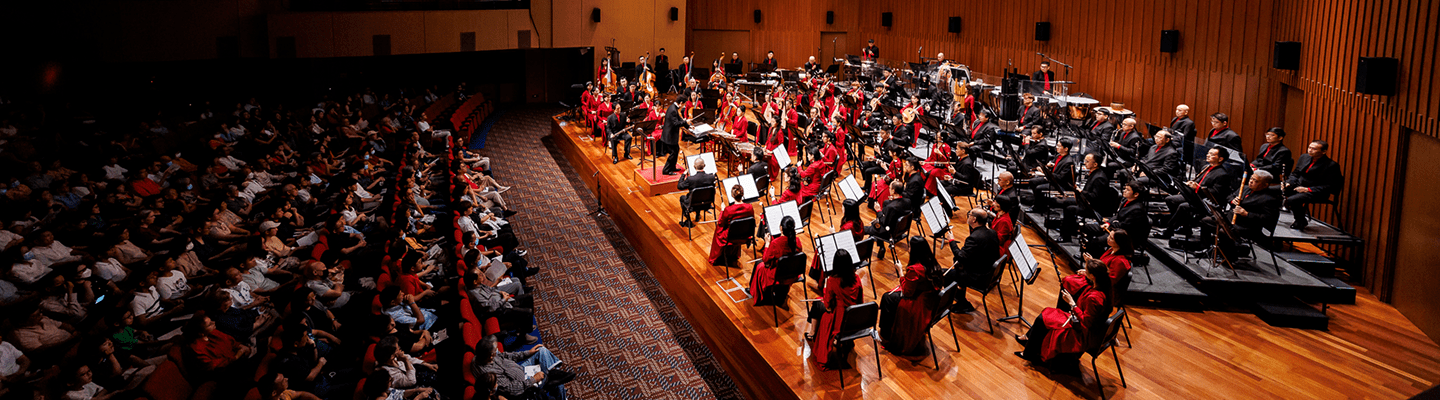

Chamber Charms: Pizzicato invites audiences through an awe-inspiring journey across ever-changing time and landscape.

Antiphonal Flower Song for pipa and yangqin composed by Zhang Xiaofeng takes inspiration from a Chinese folk song that conveys a spirited dialogue between a pair of lovers or good friends on the traits of flowers that bloom each season. The characteristic spontaneity and merriness are conveyed through spacious phrasing, seamless exchanges and role playing between both idiosyncratic instruments. It is stimulating to hear how the two voices alternate between harmonization, unison and counterpoint, occasionally emulating the sound of an accompanying drum as well.

Next, the ruan family takes center stage in composer Liu Xing’s seminal work for the instrument, Mountain Song. Shan’ge (“mountain song”) is a genre of Chinese folk song usually associated with high and penetrating timbre, expansive melodies, or relatively free rhythms. In contrast, Mountain Song appears to be more stylistically similar to country rock guitar music, where soloistic, guitar-inspired undulating runs and syncopated beats imbue it with a timelessly fashionable and impressive flair. Chen Zhe’s arrangement for ruan ensemble enhances all the above traits and creates new harmonies, further foregrounding the depth and resonance of this remarkable instrument.

Also deeply rooted in folk life, the third piece Three Six is well-known composer Gu Guanren’s 1961 plucked string arrangement of one of the eight great pieces of the Jiangnan Sizhu (silk and bamboo) tradition. This elegant musical genre appeared around the Ming Dynasty and primarily prevailed in parts of Jiangsu province, Zhejiang province and Shanghai. Implied by its name, Jiangnan Sizhu is reflective of picturesque Jiangnan with its elegant and harmonious playing style. The ensemble consists of stringed and wind instruments, comprehensive and colorful in sound. The main feature of the tradition is the collective ornamentation of one main melody, which can reveal the dynamics, cohesion and chemistry between musicians. Born in Jiangsu province, Gu Guanren’s lifelong passion in exploring and disseminating cultural traditions through his music has led him to create some of his most iconic works. Three Six, which highlights the crystalline radiance of plucked strings, has since been cherished as a representative work and enjoyed great popularity worldwide.

With the mystical worlds of celestial beings in mind, Heavenly Fragrance of Gandharva by composer Chen Xinruo distinguishes itself from the above lineup. In Indian religions, gandharvas refer to divine musicians that abstain from alcohol and meat, continuously emanating fragrance. According to early Buddhist texts such as the Dīrgha Āgama and Avadanasataka, gandharvas sing praises of gods while accompanying themselves with lapis lazuli lutes high above the clouds. The sheer magic of this imagination is brought to life through a “lute-full” ensemble of pipa, ruan, as well as yangqin in this work, which also reminisces aspects of Indian classical music such as melodic fluctuations, pitch-bending and strong rhythmic groove.

Transporting the audience back earthside to the warmth breath of the living, Narati spotlights the plucked strings in a different context. Located in Xinjiang, home to many ethnic groups, Narati grassland is one of the most beautiful grasslands in China for its mountainous scenery. In Narati,composer Liu Chang draws musical influences from Kazakh and Tajik cultures that morph into stirring melodies and dance-like grooves. The emphasis on performance dexterity immediately recalls timbres of lutes associated with Central Asia and commonly played by the Tajiks, Kazakhs, Uzbeks such as the rubab, dombra and tanbur etc., coalescing diverse traditions in a musical melting pot.

For tonight’s concert, SCO Composer-in-Residence Wang Chenwei has specially rearranged his work Childhood, which was written at the age of 16. The sense of nostalgia—longing for a simpler, happier past, and bittersweet experiences transitioning to adulthood drift gently through animated motifs, songful lyricism and blossoming, romantic harmonies in the music. Such sincerity in expression is retained in Chenwei’s subsequent, beloved works that are now staples of Chinese orchestral repertoire, such as The Sisters’ Islands and Confluence, even if these works are more known for their explorations of cultural identities in and around Singapore.

What better way to conclude the concert than with composer Jiang Ying’s Dunhuang, which celebrates thousands of years of musical heritage on the Silk Road with the invitation of bowed, wind and percussion instruments? Some of these Chinese instruments (such as pipa, bili, dizi, and drums, etc.) were thought to have evolved as part of cultural exchanges along the Silk Road, which connected the Central Plains of China to the Western Regions, Central Asia, the Middle East and beyond. Dunhuang, an ancient city that served as a cultural and commercial hub on the Silk Road, springs back to its brilliant, bustling life through the piece inflected with tonalities of the Western Regions. May the yearning and aspiration for the precious and beautiful through each piece of Chamber Charms: Pizzicato be continually etched in the hearts of the audience.